ORTLER [n.]

> highest mountain in the Eastern Alps (3905m)

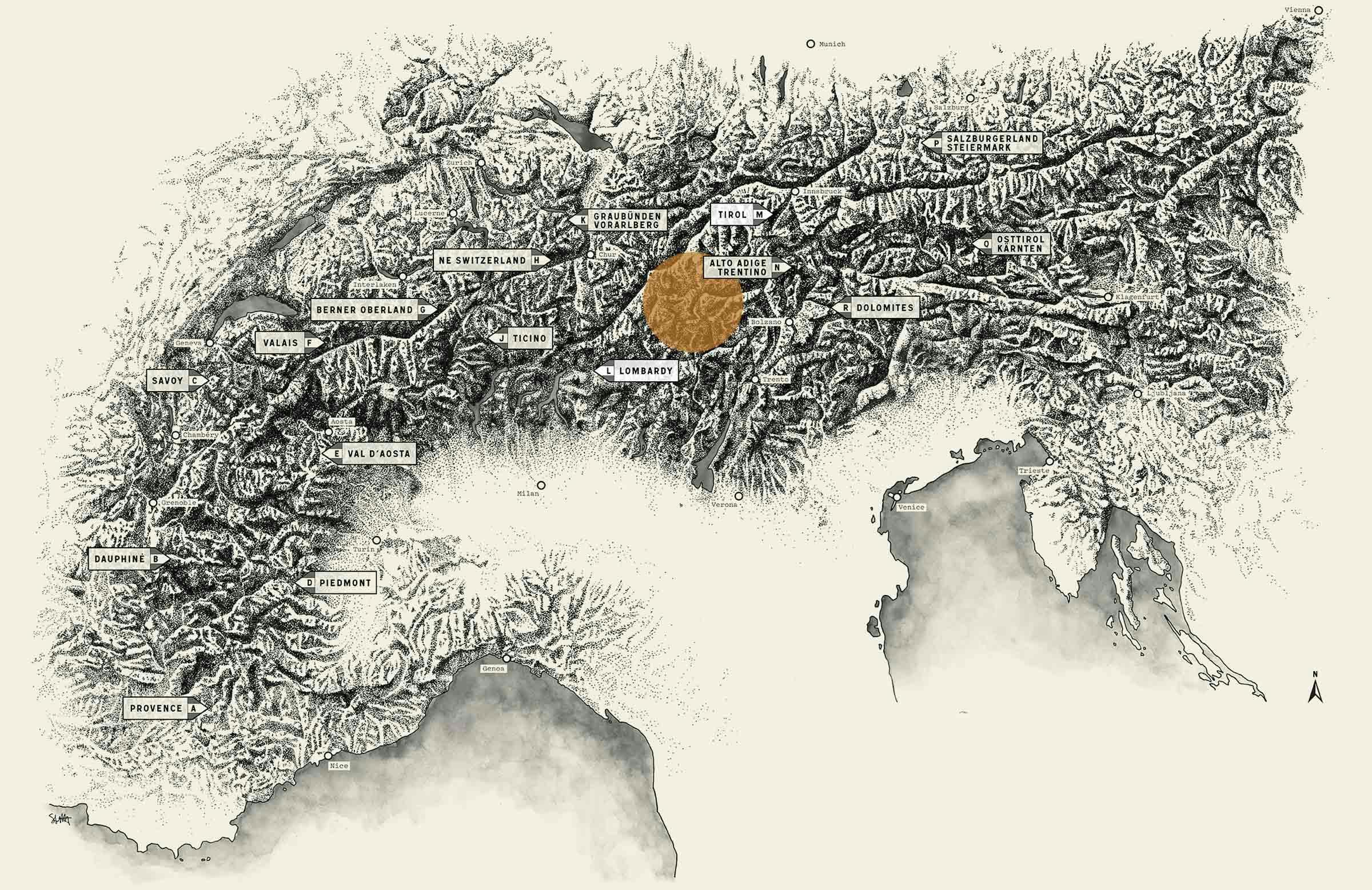

> main peak of the Ortler Alps

“…the impressive line-up of Königspitze, Zebru and Ortler, from the north-east, is known as ‘das Dreigestirn‘ (the three heavenly bodies)”

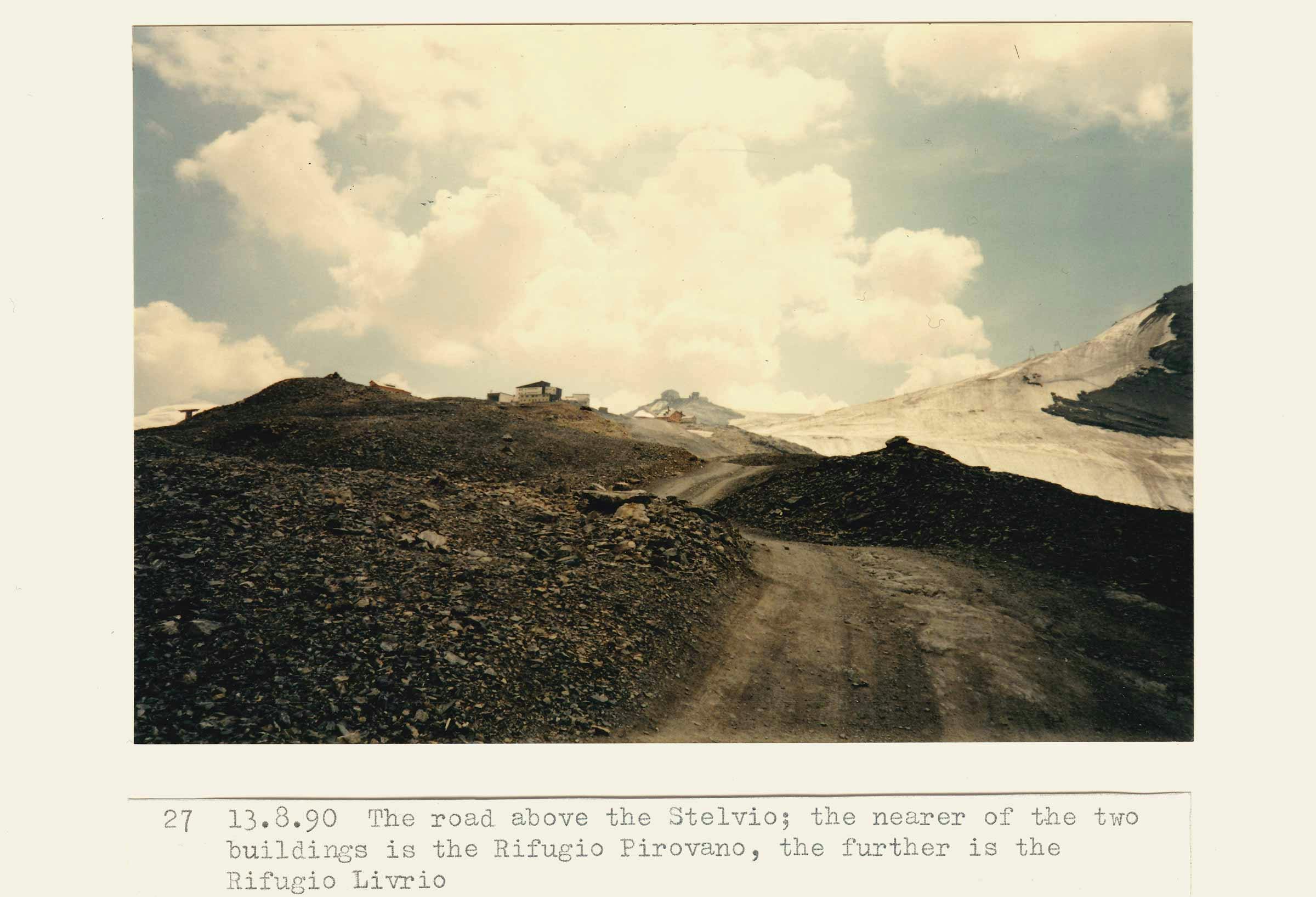

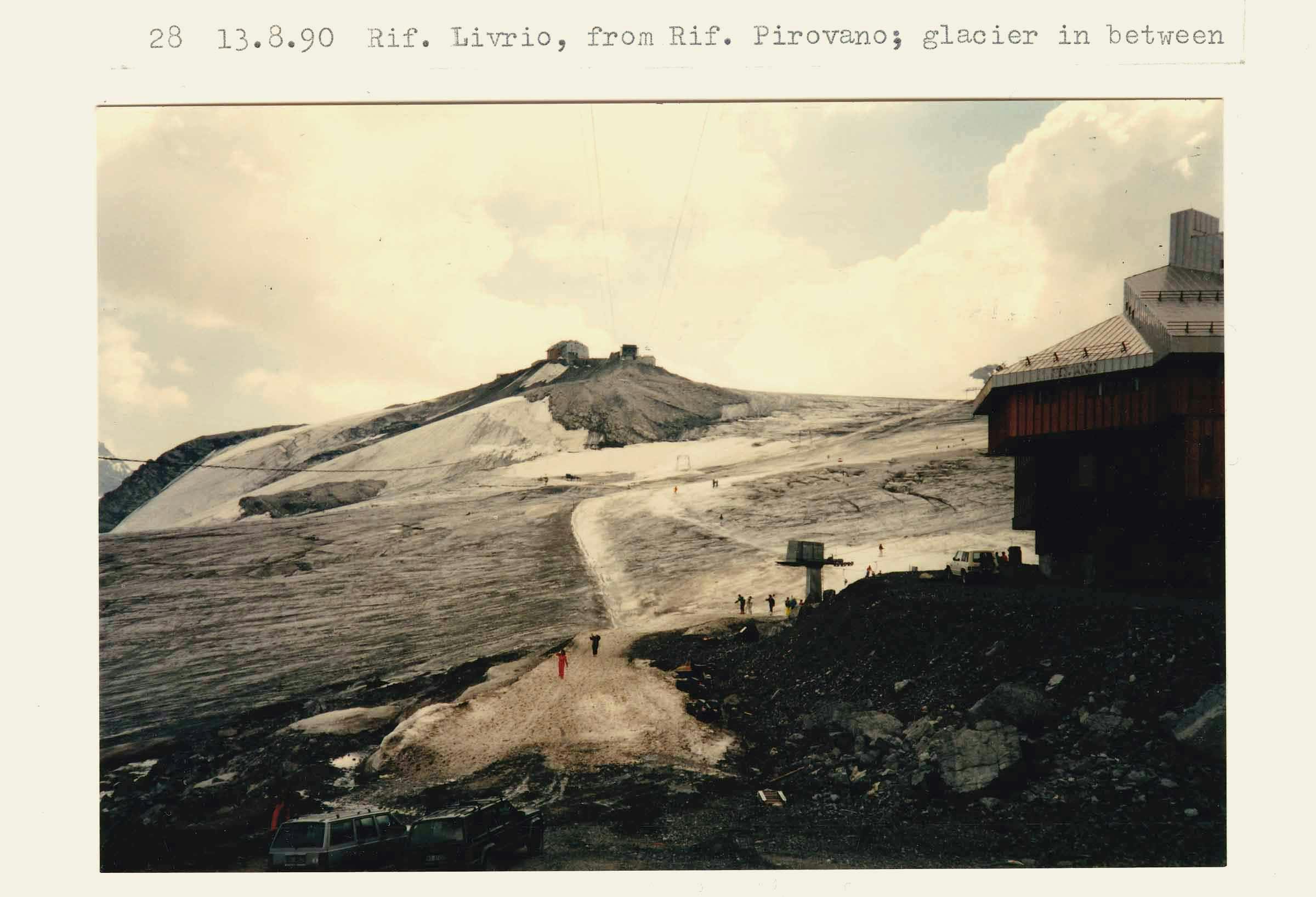

There we were. We had made it from Sheffield to the top of the Umbrail Pass – the junction where it joins the Stelvio Pass, crossing from Switzerland to Italy – and finally jumped out the Pannier Van to wander in the Ortler breeze and soak up our new Stelvio surroundings.

The van had just about revved its way up the steep ribbon of tarmac with Jordan, Dave and I, five bikes, bikepacking kit and a couple of emergency panettones in tow. Bormio, our next and final stop – where we’d leave the van and meet up with Beth and Jess – was 18km/1200m below us and the col highpoint of the Stelvio Pass 3km/300m above us, through the hamlet of typical mountain-pass-weather-beaten Albergo-Ristorante buildings.

How had Fred travelled to this mountainous void?

Fred Wright, intrepid author of the Rough Stuff Alps book (reprinted in 2018), spent the middle weeks of August 1990 in this area, riding and hiking with his trusty steel road-touring bike – researching and documenting routes before publishing what would become the underground bible for off-road riding in the Alps.

The above photo of the Ortler, Zebru, and Konigspitze stood out for me when Max Leonard first showed me Fred’s amazing photo albums; a photo I’d go on to draw for the Rough Stuff Alps book reprint project, alongside the book’s location map. In the wake of that illustration work, I spent some time researching how could we curate a bikepacking trip around this photo of Fred’s … and with colleague Dave, Beth, Jess, Jordan, South Tyrol and Bormios’ help, we hatched plans for a four-night adventure…

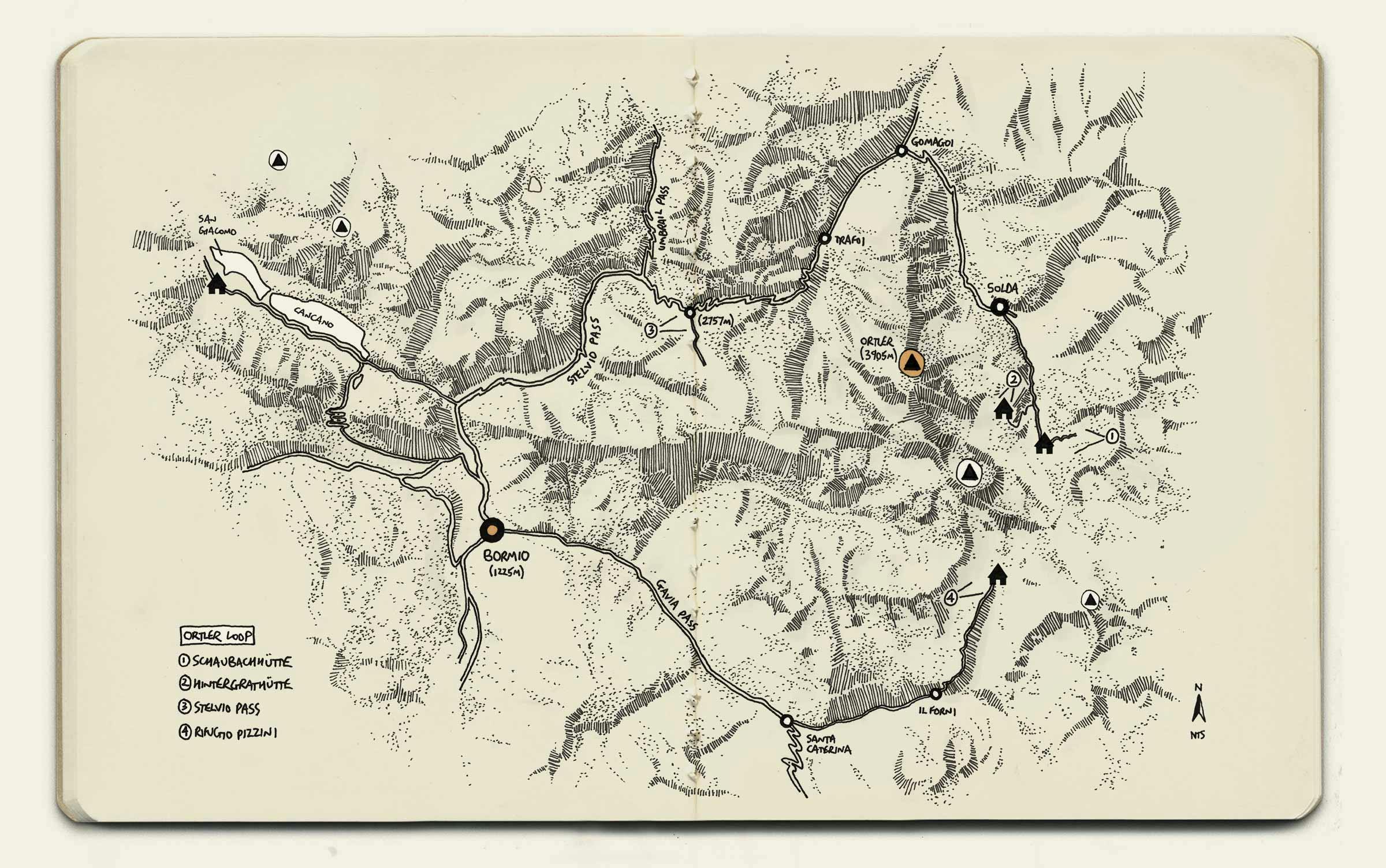

The aims for our Ortler hut-to-hut bikepacking trip:

– to seek the view of ‘The Dreistigirn’ from Fred’s photo, by retracing a couple of Fred’s routes (N6 and N12) from Rough Stuff Alps…

– to add our own Rough Stuff Alps route – let’s call it N15, or NTiramisu as you’ll later find out…

– to ride bikes and enjoy spending time with two new touring companions – Beth and Jess…

– to ultimately loop the Ortler peak, visiting old postcard views (1-4) and staying at strategic mountain huts in the various valleys. After studying maps and apps, there was only one way to make it work for us on bikes: riding the ancient Stelvio Pass both ways, for glaciers and the Eastern Alps’ biggest peaks stood in our way. Some of you will notice that you can close the loop, but you’d need the intrepid-ness of Fred Wright and the glacial skills of local celebrity climber, Reinhold Messner – who we’ll come onto later.

Anyhow, dusk was due, so we got a shuffle on and made it to down to Bormio for 16.00. The five of us still needed to sort bikes, pack, and ride 50km/2100m+ that first evening because we needed to be in Solda for an early start the next morning. Climbing and descending the entire empty Stelvio Pass at twilight was a special experience…

As documented by Professor F Umlauft in 1889: “The Ortler Alps cover an area of 780 square miles. The western portion belongs to Lombardy, the eastern to Tyrol. The sedimentary rocks here rise in an exceptional manner, higher than the crystalline rocks; the culminating point, the Ortler, belongs to the former class.” The Stelvio National Park, where this trip’s bikepacking route lay, pretty much centres around this Ortler peak (3905m) which, with its cluster of nearby peaks and stunning glaciers, makes up these Ortler Alps…

“A cyclist will often look at a map, see a road running up into the mountains and ending there … Rough Stuff Alps will show cyclists that often they need not be discouraged, and that with the right equipment and variable amount of effort they can go up the valley and over into another valley, then get back on their bike and on their way” FW

On leaving the bounds of Solda and riding the rough stuff track further up into the mountains, we were straightaway surrounded by these 4000m peaks – immersed amongst scree slopes and glaciers. The tightness of a 35mm lens appears to have captured this experience perfectly, as Jess and I quit pedalling and hiked the last super-steep section of Fred’s track up to the Schaubachhutte and Madritscherjoch. Beneath blue skies, the glacial greys and mountain madders shone – etched by the warren of waterfalls and stubborn snowpack, fading into the alpine-grass greenery that lined our tracks.

The view, Fred’s view and photo, across to the three heavenly peaks was just as I expected and it felt somewhat surreal to be there looking over the Ortler, next to Jordan and hibernating piste-bashers. I attempted to spot details that were different between now (2018) and Fred’s photo (1990) but the distant, echoing crashes of seracs and rocks we witnessed all afternoon were testament enough to the slowly changing Alpine environment…

“Beneath blue skies, the glacial greys and mountain madders shone – etched by the warren of waterfalls and stubborn snowpack, fading into the alpine-grass greenery that lined our tracks…”

Earlier that first morning, in Solda, a local guy asked us what and where we were riding to on our loaded bikepacking bikes. “Madritscherjoch” we replied, before mentioning we planned to then stay at Rifugio Coston for the night. He went on to tell us that his friend, the local XC MTB champion, had only just about managed to descend the track to the hut, let alone climb it. Not for us I realised, confirming suspicions from map work at home.

Rifugio Coston was an important hut to reach and spend the night though – the hut was, and still is, an integral part of the Ortler Alps’ climbing infrastructure. The Ortler peak itself was first climbed in 1805, by Josef Pichler – a local chamois hunter – who had to walk up from Gomagoi and stay in priest lodgings. There was nothing here at that time; the first tourism in Solda seemed to really start in the mid-1800’s, similar to the rest of the Alps. Rifugio Coston was first built in 1892 and was rebuilt in its current position in 1922, just in time for Hanz Ertl and Franz Schmid to stay and use the hut as a base to successfully summit the north face of the Ortler, for the first time, in 1931…

“with my Rough Stuff Alps guide, the aim was to narrow the gap between the cyclist and the walker … for access to remote places, peace and solitude” FW

There are a couple of route options to the hut from both Solda and the Schaubachhutte. We made a group decision to descend to the middle cable-car station, assess the situation and leave the bikes at the foot of the track (carrying up our kit for the night in our bike bags) if needed. An hour into our hike up to the Coston hut we had our somewhat inevitable Ortler Yak experience, having caught wind that these shaggy beasts would be up here after seeing the “DON’T GET WITHIN 10M OF A YAK” signs. Later we found out it was Reinhold Messner that introduced these Tibetan Yaks to the valley around Solda, who spend their days on the pastures up and around the mountain huts we were visiting. At over 2500m, this was akin to the altitude they were used to.

A hearty-hut-three-course dinner, cold jugs of beer, rounds of local Genepi and socialising in the communal space, with openly Welsh-phobic Austrian climbers, awaited us that evening. As usual on these trips our first mountain hut experience of the trip lived up to great expectations.

The promise of a dawn #coffeeoutside had us up early the next morning, not least because we had a tour at the Ortles Messner Mountain Museum back down in Solda booked for mid-morning…

“Messner calls the MMM project his 15th eight-thousander”

Reinhold Messner is one of the world’s famous mountaineers: the first to climb Mt. Everest solo, and the first to climb all the world’s fourteen 8000m peaks. He hails from South Tyrol and, whilst he is not from Solda, given his connection to this mountaineering centre in the Ortler Alps he bought a 400-year-old farm, land and buildings on the outskirts of the town 30 years ago, opening an ace bar/restaurant – Yak and Yeti – in the mid-90s.

His Messner Mountain Museum (MMM) project now numbers six sites throughout the Alps. They are not just well-located museums, they are architectural wonders and places to meet and feel at home, with the mountain as their theme. I knew of the MMMs from the prestigious MMM Corones project which, with architect Zaha Hadid, he immersed within the peak of Mount Kronplatz. According to his daughter Magdalena, the Museums’ Director, her father established the museums to “tell stories that have arisen from meetings between people and mountains – all related to his passion for the global mountain world, the history, development and future of the mountains, their protection and use, the people in the mountains and the mountain climbing that lured the first tourists to the area”.

MMM Firmian tells the story of the emergence, ascent and erosion of mountains; MMM Juval holy mountains; MMM Dolomites rock climbing; MMM Ripa mountain peoples; and MMM Corones traditional alpinism on the great rock faces of the world…

During our time in Solda, we visited his sixth museum – MMM Ortles – which is right next to his Yak and Yeti bar. Designed by a local architect and completed in 2004, this is the smallest MMM. Given its location at 1900m, directly under South Tyrol’s highest glacier “at the end of the world” as described on a 1774 map by Peter Anich, the museum’s theme is ice. The space was designed from scratch to evoke the feeling of being in a crevasse. Amongst the chilling exposed concrete sub-terranean walls, a jagged slither of a rooflight allows shards of natural light in, whilst also showing glimpses of the Ortler peak beyond. Just like being in a crevasse, I can only imagine. Messner says it ranks amongst his favourite spaces – totally reflecting the connection between the museum content and outside world, and therefore celebrating the first ascent of the Ortler over 200 years ago.

On the subject of ice, that afternoon after eating too many delicious Canederli – a Tyrolean bread dumpling speciality – at Yak and Yeti we were headed back over the Stelvio Pass, up to 2800m, where summer skiing is even a thing…

If a road is closed for half of the year, you can expect it to be a goodun and the Stelvio Pass sure lives up to its reputation. Riding the lengthy, meandering pass at a quiet time of day makes for an ace, challenging experience. Behind the Col de l’Iseran in France by a mere 13m, the Stelvio Pass is the second highest paved road pass in the Alps – the Ortler Alps’ jewel – connecting South Tyrol to various valleys, Bormio, and routes into Switzerland.

Professor Umlauft (him again) offers good insight into the Pass from 1889: “a bridle-path led over the Stilfer Joch as early as the fourteenth century” before “the present high road was made by the Austrian Government in the years 1820-24 to connect the former Austrian province of Lombardy with the rest of Austria … It is nineteen feet wide throughout, and has a gradient of only three to seven percent, and in the most difficult parts ten percent … this gentle ascent is attained by means of numerous windings (forty-six in Tyrol, thirty-eight on the Lombardy side) by which the road climbs [1870m] up and down the mountains…”

“…Wherever the road borders upon an abyss, parapets, either of wood or brickwork are constructed, and where avalanches frequently occur covered galleries are built, or else the road is blasted out of the rock in such a way that the rock itself forms a roof over it…”

Before the end of World War I, the Stelvio Pass formed the effective border between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Italy, turning the Ortler Alps into a conflict zone, widely known as the highest front line. After 1919, with the expansion of Italy, the road lost its strategic military importance, however the increasing levels of foreign and tourist traffic prevented the road’s demise. Today, the road opens, with ceremony, in May and closes for winter in November.

Umlauft goes on: “The portion of the Stelvio Road which leads south of the pass into Italian territory is, it is true, somewhat less picturesque than the northern part, but the road itself is not any less interesting than on the opposite side.” The descent back past the Umbrail Pass junction “through the desolate limestone cauldron, destitute of any kind of vegetation, to the fourth and third cantoniera” is some of the best few minutes I’ve spent on a bike. TCR 2018 winner, James Hayden, tells me he almost hit 100kph on that long stretch. The road then winds down steeply, and through a section of galleried tunnels to Bormio – “the warm springs of which were used by the Romans at the time of Pliny.”

No hot springs for us. Our five-strong bikepacking squad headed onwards to the next hut on the shores of Lago di San Giacomo, where we arrived in the dark and devoured all the pasta and vino rosso we could…

Passing back through Bormio the next morning, we were lucky enough to have a private tour of the Braulio production facilities – a famous herbal amaro drink that originated in the town in 1895 – which stretch 25m below the Via Roma where we left our bikes. Riding the Stelvio Pass, you actually pass Mount Braulio, through the Braulio valley, which is where the herbs to make the drink came, and still come, from. About 1,000,000 litres of Braulio is made in these Bormio cellars each year. To make the amaro drink:

1/ water, alpine herbs and alcohol are mixed in 18 vats for 40 days

2/ the liquid is separated from the herbs with old wooden presses before sugar and caramel is added (waste herbs are sent off to make domestic aromatic products)

3/ this liquid is then left in 45-50 year old Slovenian Oak barrels, of which they have capacity for nearly 500 now

4/ once the liquid has aged for 15 (normal) / 24 months (reserva) it is refrigerated, filtered and bottled

The recipe is a secret, of course.

Braulio has an acquired taste, for sure. Once prescribed as a herbal pharmaceutical remedy, it is now seen very much as a digestif or, when mixed, an aperitif for hardy (/desperate) souls. We decanted a bottle of Braulio Reserva into a more transportable Sigg bottle and took it up to toast our last night at Rifugio Pizzini…

From Bormio a left off the Gavia Pass, and left again, leads to a stunning gravel track that winds back up, alongside cowbell clanging cattle pastures, to the foot of our big Ortler Alp peaks – completing our loop. With a couple of kilometres to go, the welcoming sight of the hut appears up high and centre at the head of the valley, beneath the Konigspitze (Gran Zebru). If you don’t like steep climbing on a bike, or hiking with a bike, this is definitely not a route for you…

tiramisu |tɪra mɪˈ su|

[n.] pick me up

We were riding in Northern Italy, so a mountain hut tiramisu kind-of had to be done. At Pannier, we always like to attempt a fancy drink / foodie dish up in the mountains – the challenge of sourcing ingredients, carrying them up by bike (safely), and making it happen appeals to us.

Now, I’ve made countless tiramisu in my life, but never out in the open with bikepacking camp cookware. Ideally you make one the day before and leave it chilled, for the flavours to mingle and texture to go all lovely. We didn’t have this luxury so instant tiramisu it was: no eggs; no whisking; no cocoa; no booze. Just cowboy coffee and sachet sugar, mascarpone, and a sprinkling of 3-in-1 coffee sachet for the top. We did, however, find the proper savoiardi biscuits (posh Italian sponge fingers)…

…spot the savoiardi biscuits

>> Phone ahead, to make sure the huts are open and have space. But importantly, just to let them know to expect you, and your appetite.

>> Get onside with the Hut Warden as best and soon as possible.

>> Reserve a bed early doors.

>> Use the Boot / Kit Room. Hut Slippers are a must. The pinker, and Croc-ier, the better.

>> Bring: Cash (more than you think – the infrastructure required to run these huts justifies it); Sketchbook (for hut stamps, diary keeping … and sketching); Towel; Sleeping Liner; Ear Plugs (communal sleeping); Headtorch; Wet Wipes.

>> Always sample the hut’s home-brew Genepi / local liquor.

>> BYOB – bring your own breakfast. Dinners are hearty, tasty and amazing. Breakfasts not so much, especially to set you up for a day in the mountains.

>> Do not leave cheese in communal spaces.

Anything we’ve missed, or you’d like to add, do let us know in the comments below…

Our final morning to Bormio was an easy one that barely required much pedalling. Usually we avoid out-and-back rides, but when the hut overnight was as stunning and the descent as fun as it was, there was no point beating ourselves up about it. Back in Bormio, it was time to celebrate … with an ice cream.

Next stop was Sheffield in the van, via the Maloja and Splugen passes…

Over & out!

(…any questions? Do comment below and we’ll get back to you)

Words & Illustrations

Stefan Amato

Photos

Jordan Gibbons

Tourers & Additional Photos

Jess Duffy

Beth Hodge

Dave Sear

Map

Stelvio National Park – Kompass 072

Books

Rough Stuff Alps – Fred Wright

The Alps – Professor F Umlauft

Messner Mountain Museum – Magdalena Messner